Dr Janine Kripner, Volcanologist and Science Communicator, will oversee this programme and will coordinate collaboration with IGN, Instituto Geográfico Nacional (Spain).

Over 29 million people worldwide live within just 10 km of active volcanoes, and good, widely-disseminated information is key to mitigating risk. The Canary Islands are an active volcanic region, but much of the population does not know enough about the potential hazards or risks involved. How do you quantify volcanic risk in a territory? And how do you ensure a population is fully informed and resilient, especially when volcanic eruptions do not happen very often?

In previous years, our students have studied a town’s historical exposure and current volcanic risk, preparedness, hazards, and susceptibility. In 2025, the focus was on Garachico, in North West Tenerife, in advance of a full-scale eruption exercise carried out by the Canary Island authorities in the town. In 2024, our students studied Vilaflor, the highest town on Tenerife, situated just South of the Mount Teide national park. This year, the selected students will participate in and design a broad study of a town along the North West rift zone, where risk is highest on Tenerife.

-

Learn to quantify historical eruptions (e.g., their volume, the distance travelled by lava flows, the thickness of tephra deposited, the eruption duration)

-

Hands-on experience with volcanic monitoring data types and the interpretation of this data

-

Participate in a “real-time” emergency management simulation

-

Fieldwork on several historical mafic eruptions and you will learn how to identify deposits from different and sequential eruption phases.

-

You will also be designing and carrying out a short survey to better understand how the authorities may improve the volcanic resilience of tourists to the island

Previous years’ survey research produced interesting results. The 2022 GeoInterns were co-authors on this paper, which was published on ResearchGate, and last year’s research was presented at VulcanaSymposium by our local scholar Javi Diaz. Our research enables us to collaborate with a range of institutions and emergency managers in advance of a future eruption on the island.

It is so important to #engage in the communities you work for. This was my @GeoIntern team and me in #Vilaflor listening to local voices for our work with @GeoTenerife@wisdom72954845 @volcanic_souna @JackGloverGeo @JaviDiaz_19 @BrookePiccoli#SciComm#Volcanoes#Geology pic.twitter.com/PID9xq67fJ

— Isabel Queay (@IQueay) August 20, 2024

Previous research of programme C

Volcanic Resilience of Garachico, Tenerife

A Scientific Report (2025)

Ash Harden ¹, Emma Read², Jessana Yandell³, Jonathan Jativa-Calle⁴, Leah Gomm⁵, Michael Hill⁶, Scott Spires⁷, and Willow Lehrich⁸

1 University of Bristol

2 Oxford Brookes University

3 Bangor University

4 University of Durham

5 University of Plymouth

6 University of Liverpool

7 University of East Anglia (UEA)

8 Scripps College

Abstract

Volcanic resilience research explores how communities anticipate, absorb, and recover from eruptions by integrating hazard assessment with social vulnerability and communication analysis. Understanding both the physical and human dimensions of volcanic risk is essential for effective preparedness and mitigation.

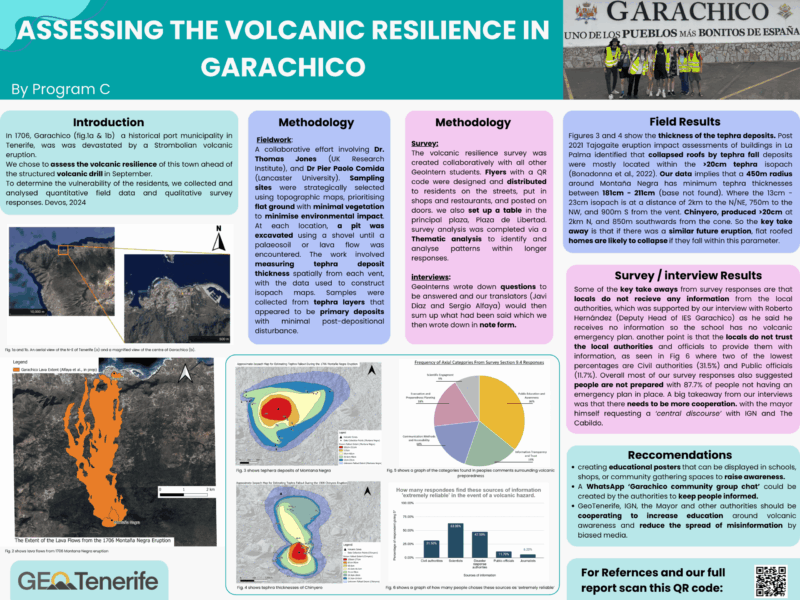

Garachico, a historic port town in northwestern Tenerife, was devastated by the 1706 Montaña Negra eruption, which buried much of the settlement under lava flows. This study assesses the town’s volcanic resilience ahead of a planned volcanic drill, combining geological and social data to identify where physical hazards intersect with community vulnerability. Two complementary approaches were applied: (1) field-based measurements of tephra

deposit thickness to map hazard intensity and (2) community surveys and interviews to analyse preparedness and trust in authorities. Fieldwork involved excavating shallow pits at minimally disturbed sites to measure primary tephra deposits and construct isopach maps. Results show that tephra thickness varies substantially across the study area, with Montaña Negra displaying deposits exceeding 1.8 m near the vent and 13–23 cm up to 2 km away.

Chinyero deposits reached over 20 cm at 2 km, consistent with past hazard models. The data suggest that a future eruption of similar scale could again produce significant roof-loading and collapse risks for low-lying, flat-roofed buildings.

The social survey and interviews revealed clear patterns of vulnerability. Most respondents (87.7%) lacked an emergency plan, and trust in official information sources was notably low—only 11.7% considered local authorities reliable. The most trusted sources were friends and family (31.5%) and scientists (20%), indicating a reliance on informal networks. Residents reported limited access to official information and perceived poor coordination

between scientific institutions and local government. Local educators confirmed that schools currently receive no structured volcanic information, highlighting a critical communication gap.

Our recommendations include establishing community-led communication channels (e.g., a “Garachico Community Group” on WhatsApp), producing local educational materials, andstrengthening collaboration between scientific institutions and municipal authorities. This multidisciplinary approach offers a transferable framework for enhancing volcanic resilience and participatory risk governance in other hazard-prone communities across the Canary Islands.

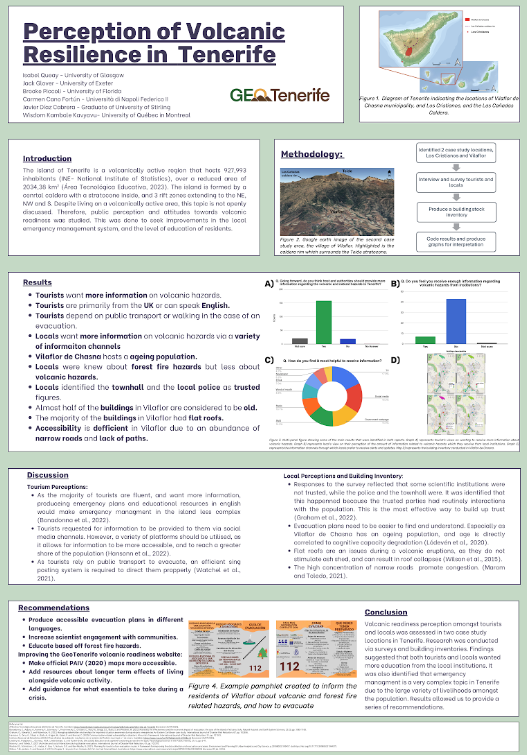

VOLCANIC RESILIENCE IN VILAFLOR DE CHASNA (2024)

Queay, Isabel¹, Glover, Jack²; Piccoli, Brooke³; Cano Fortún, Carmen⁴; Cabrera, Javier Díaz⁵; Kambale Kavyavu, Wisdom⁶

¹University of Glasgow, ²University of Exeter; ³University of Florida; Università di Napoli Federico II⁴; Graduate of University of Stirling⁵; University of Québec in Montreal⁶

Abstract

Volcanoes pose a significant threat to the people of Tenerife, and the people who live the must have a certain amount of resilience to tackle this. This is shown by the 2021 eruption of La Palma, where many of the residents are still recovering from the impacts today. This report looks at the municipality of Vilaflor de Chasna, how much the people are aware of the volcanic risk, and how they would react when an eruption does happen. Data collection involved creating a survey and asking the residents of the town questions about demographics, volcanic knowledge, who they would contact in an emergency and how they feel about the current emergency systems. We asked questions that would allow us to gauge the vulnerability of the town, such as how many dependents residents have and whether they would require assistance during an evacuation. Additionally, we also interviewed some of the local figures such as the Mayor, Nuns and Firemen who gave information on the volcanic readiness of the town. From this data, we were able to learn some key information about the local volcanic knowledge and the institutions that people trust to give accurate knowledge. As we completed our data collection we were able to reflect on some of the issues that we faced. For example, the lack of Spanish-speaking researchers in our group, as they were the ones who could effectively talk to respondents, and the limited amount of time that we were able to spend in Vilaflor de Chasna. It is critical that volcanic resilience is built within the population of Tenerife in order to mitigate the impacts as much as possible; this can be achieved through education of the population and targeting weak spots in the current emergency plans.