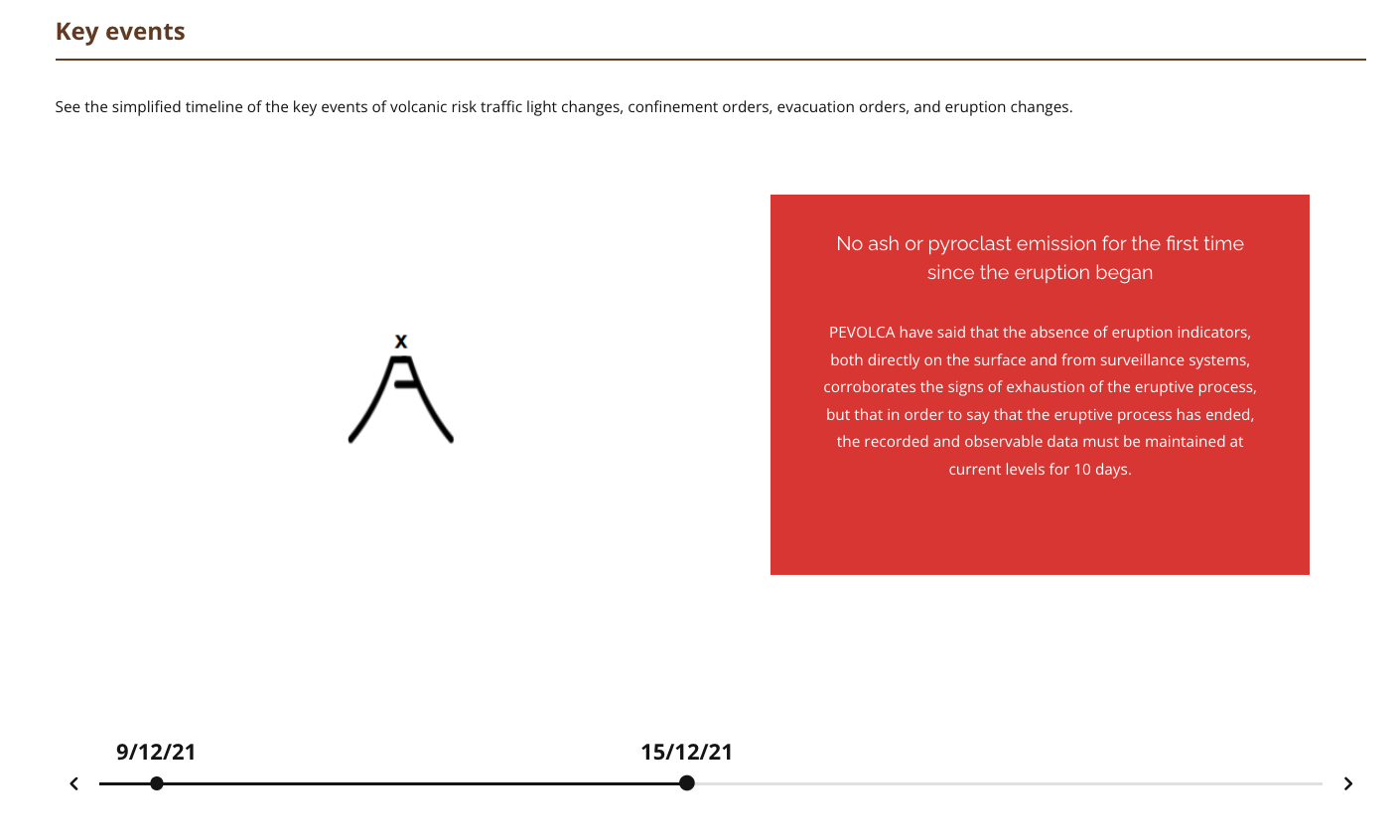

Most recent

La Palma Reconstruction – January 2026

Faults identified during the eruption continue to 'creep' - New eruption forecasting methods from La Palma highlighted by UNDRR - Students participate in water quality measurements - More than 1,100 families now returned to Puerto Naos and La Bombilla - Aid for second homes starting to be delivered - €400,000 for home construction in Los Llanos - Demands for aid from the 'Volcano Law' - Ongoing aid for affected businesses - LP-2 reconstruction commences with challenges and expropriations - La

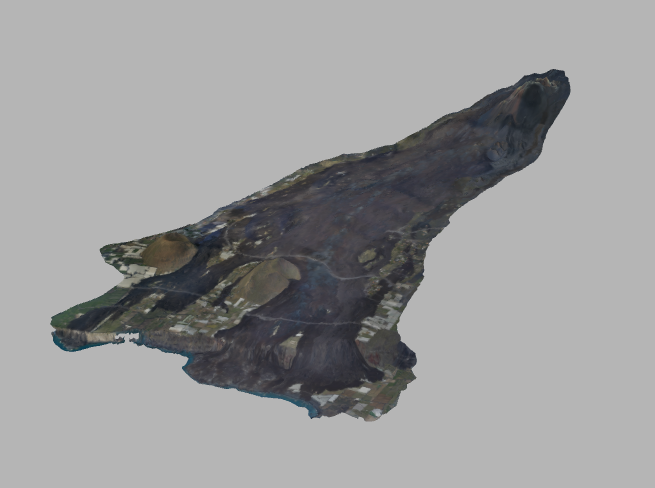

Volcán de Tajogaite (2021) Eruption and Reconstruction

GeoTenerife aims to tell the unheard human stories of the people affected by the 2021 eruption of the Volcán de Tajogaite, La Palma. Through our collaboration with Alexander Whittle of New Light Studio, GeoTenerife has produced two documentaries LAVA BOMBS: Truths Behind the Volcano and LAVA BOMBS 2: The Reconstruction.

The 2021 Tajogaite eruption was the largest and most destructive eruption in La Palma for the last 500 years. It caused around €1 billion in damage, displacing over 7,000 people, and destroying 3,000 buildings, 2,000 of which were people’s homes. Here are some of VolcanoStories helpful summary videos:

A collection of interviews with witnesses of the 2021 La Palma Eruption, conducted by GeoTenerife. These interviews were later used in the Lava Bombs: The Truth Behind the Volcano documentary.

To help put the science in context and counter sensationalism GeoTenerife was involved in social media live streams and news interviews with local, national and international media outlets during the volcanic eruption of La Palma. Here are the playlists which document our work.

Charities to support affected residents

Here are the charity campaigns we have supported/run for the affected residents of the La Palma eruption

The conversation: Cuna del Alma, the SeaLab and the Turtles

Quote from GeoTenerife on 11 December, 2025, 10:59 amOpinion piece

By Damien Lim

and Sergio Alfaya, GeoTenerife

The Canary Islands are marketing themselves as a paradise of biodiversity and sustainable tourism. But the story of the Puertito de Adeje SeaLab reveals a very different truth: a pattern in which local authorities exploit environmental restoration initiatives for public relations, only to erase them when real-estate interests come calling.

The story begins in 2004, when Tenerife faced a silent ecological collapse. An invasive sea urchin species was devastating the island’s marine ecosystem, consuming the algae ecosystem that once supported a rich coastal food web. In response, diver and conservationist David Novillo founded the Océano Sostenible Association, launching a hands-on effort to restore marine life in Puertito de Adeje. They called it the SeaLab.

What happened next was extraordinary.

Océano Sostenible’s efforts in destroying the sea urchin plague were successful. As the algae ecosystem recovered, marine wildlife started coming back to Puertito. Sea turtles began appearing once again to feed, grow and reproduce in the safety of the bay, some traveling from as far as Mauritania, Cape Verde, and even Costa Rica. The SeaLab team monitored the turtles’ health, collaborated with the La Tahonilla wildlife recovery center, and regularly assisted injured individuals. Volunteers poured in by the hundreds.

Tourists noticed.

So did the authorities.

By 2009, both the Spanish Directorate General for the Coast and the Canary Islands government were on board with the project. In 2012, the directorate even funded new seabed-surveying equipment shipped from the mainland. The Adeje municipality promoted Puertito as the bay of the turtles, using images of David’s work in its own communications and reaping the benefits of a booming local economy centred on sustainable tourism.

The SeaLab gained international recognition, earning awards from National Geographic, the British Guild of Travel Writers, and others. David even carried out the first underwater video call ever made in the bay—exactly the type of innovation that institutions were proud to showcase.

Then, abruptly, everything changed.

When a Conservation Project Became an Obstacle

In 2014, Océano Sostenible requested a licence to use a warehouse in Puertito as a permanent base for the SeaLab. The owner was granting the space freely for the project. But despite years of public support, the Adeje municipality denied it. Only then did David learn the truth: the land had been sold years earlier, and the municipality had quietly drawn up plans for a massive megahotel as far back as 1998.

The same authorities that had promoted his work were now preparing to displace it.

For four years, Océano Sostenible battled with the municipality for permits—battles they ultimately lost. In 2018, exhausted, the SeaLab was forced to shut down. Without monitoring, habitat maintenance, or turtle care, the population in the bay quickly collapsed. David returned to find broken shells, dead hatchlings, and no meaningful response from local officials.

The “bay of the turtles” was still being marketed.

Only the turtles were gone.

"There is a fantastic quote attributed to Walt Disney that says, “Think about whether what you are doing today is bringing you closer to where you want to be tomorrow.” Here, we could say to our politicians, with Mr. Disney's permission, that they should think about whether what they are allowing today is bringing them closer to the island they want to be on tomorrow..." David Novillo

The New ‘SeaLab’: Sustainability as Marketing

The megahotel project continued moving forward. When its 2019 Urbanism Plan was released, David found yet another surprise: it included a “SeaLab” of its own. But this version—less than 500 m² (about a third of an olympic swimming pool), squeezed between beach services and allowed to hold electrical transformers and pumping stations—had nothing in common with the conservation programme it was appropriating. It was a branding tool, not a scientific facility.

Construction began in 2022. To make way, a Site of Geological Interest with a high protection priority declared by the Spanish Survey (IGME-CSIC) is currently being bulldozed. It is the most-sponsored site in Spain on IGME’s Adopt A Rock Campaign, backed by leading international experts.

Plans include dumping artificial sand onto the beach—an irreversible intervention guaranteed to destroy what remains of the restored habitat.

Yet the promotional materials remain the same: “turtles, science, sustainability, innovation.”

The real story is far darker.

What Puertito de Adeje Reveals

The case of Puertito de Adeje is not only a story of one bay. It is a warning for the Canaries.

It shows how local governments can publicly embrace grassroots conservation while privately advancing projects that will erase the ecosystems those citizens fought to restore. It shows how “sustainability” can be weaponized—reduced to a marketing slogan that obscures environmental destruction and rewards speculative development.

Most painfully, it shows how easily decades of volunteer-led ecological recovery can be undone.

Puertito de Adeje was not destroyed by neglect.

It was destroyed by choice.

A Call to Protect What Remains

The Canary Islands are nearing a point of no return. If genuine conservation continues losing out to short-term tourism investments, there will soon be nothing left to market—not ecosystem, not turtle habitats, not the last virgin beaches of southern Tenerife.

The story of David Novillo and Océano Sostenible is a testament to what local communities can achieve in collaboration with tourists when given space to protect their own ecosystems. David’s work was funded by tourism, as visiting divers paid for the SeaLab’s operations and participated in the work. A true example of sustainable tourism. Sadly, it has become a testament of how quickly their work can be co-opted, diluted, or discarded.Puertito de Adeje could have been a model for regenerative tourism. It is becoming a monument to greenwashing and wanton destruction instead.

The question now is whether locals and the authorities will allow this pattern to continue—or whether the Canary Islands will choose a future where sustainability is more than a slogan.

Opinion piece

By Damien Lim

and Sergio Alfaya, GeoTenerife

The Canary Islands are marketing themselves as a paradise of biodiversity and sustainable tourism. But the story of the Puertito de Adeje SeaLab reveals a very different truth: a pattern in which local authorities exploit environmental restoration initiatives for public relations, only to erase them when real-estate interests come calling.

The story begins in 2004, when Tenerife faced a silent ecological collapse. An invasive sea urchin species was devastating the island’s marine ecosystem, consuming the algae ecosystem that once supported a rich coastal food web. In response, diver and conservationist David Novillo founded the Océano Sostenible Association, launching a hands-on effort to restore marine life in Puertito de Adeje. They called it the SeaLab.

What happened next was extraordinary.

Océano Sostenible’s efforts in destroying the sea urchin plague were successful. As the algae ecosystem recovered, marine wildlife started coming back to Puertito. Sea turtles began appearing once again to feed, grow and reproduce in the safety of the bay, some traveling from as far as Mauritania, Cape Verde, and even Costa Rica. The SeaLab team monitored the turtles’ health, collaborated with the La Tahonilla wildlife recovery center, and regularly assisted injured individuals. Volunteers poured in by the hundreds.

Tourists noticed.

So did the authorities.

By 2009, both the Spanish Directorate General for the Coast and the Canary Islands government were on board with the project. In 2012, the directorate even funded new seabed-surveying equipment shipped from the mainland. The Adeje municipality promoted Puertito as the bay of the turtles, using images of David’s work in its own communications and reaping the benefits of a booming local economy centred on sustainable tourism.

The SeaLab gained international recognition, earning awards from National Geographic, the British Guild of Travel Writers, and others. David even carried out the first underwater video call ever made in the bay—exactly the type of innovation that institutions were proud to showcase.

Then, abruptly, everything changed.

When a Conservation Project Became an Obstacle

In 2014, Océano Sostenible requested a licence to use a warehouse in Puertito as a permanent base for the SeaLab. The owner was granting the space freely for the project. But despite years of public support, the Adeje municipality denied it. Only then did David learn the truth: the land had been sold years earlier, and the municipality had quietly drawn up plans for a massive megahotel as far back as 1998.

The same authorities that had promoted his work were now preparing to displace it.

For four years, Océano Sostenible battled with the municipality for permits—battles they ultimately lost. In 2018, exhausted, the SeaLab was forced to shut down. Without monitoring, habitat maintenance, or turtle care, the population in the bay quickly collapsed. David returned to find broken shells, dead hatchlings, and no meaningful response from local officials.

The “bay of the turtles” was still being marketed.

Only the turtles were gone.

"There is a fantastic quote attributed to Walt Disney that says, “Think about whether what you are doing today is bringing you closer to where you want to be tomorrow.” Here, we could say to our politicians, with Mr. Disney's permission, that they should think about whether what they are allowing today is bringing them closer to the island they want to be on tomorrow..." David Novillo

The New ‘SeaLab’: Sustainability as Marketing

The megahotel project continued moving forward. When its 2019 Urbanism Plan was released, David found yet another surprise: it included a “SeaLab” of its own. But this version—less than 500 m² (about a third of an olympic swimming pool), squeezed between beach services and allowed to hold electrical transformers and pumping stations—had nothing in common with the conservation programme it was appropriating. It was a branding tool, not a scientific facility.

Construction began in 2022. To make way, a Site of Geological Interest with a high protection priority declared by the Spanish Survey (IGME-CSIC) is currently being bulldozed. It is the most-sponsored site in Spain on IGME’s Adopt A Rock Campaign, backed by leading international experts.

Plans include dumping artificial sand onto the beach—an irreversible intervention guaranteed to destroy what remains of the restored habitat.

Yet the promotional materials remain the same: “turtles, science, sustainability, innovation.”

The real story is far darker.

What Puertito de Adeje Reveals

The case of Puertito de Adeje is not only a story of one bay. It is a warning for the Canaries.

It shows how local governments can publicly embrace grassroots conservation while privately advancing projects that will erase the ecosystems those citizens fought to restore. It shows how “sustainability” can be weaponized—reduced to a marketing slogan that obscures environmental destruction and rewards speculative development.

Most painfully, it shows how easily decades of volunteer-led ecological recovery can be undone.

Puertito de Adeje was not destroyed by neglect.

It was destroyed by choice.

A Call to Protect What Remains

The Canary Islands are nearing a point of no return. If genuine conservation continues losing out to short-term tourism investments, there will soon be nothing left to market—not ecosystem, not turtle habitats, not the last virgin beaches of southern Tenerife.

The story of David Novillo and Océano Sostenible is a testament to what local communities can achieve in collaboration with tourists when given space to protect their own ecosystems. David’s work was funded by tourism, as visiting divers paid for the SeaLab’s operations and participated in the work. A true example of sustainable tourism. Sadly, it has become a testament of how quickly their work can be co-opted, diluted, or discarded.Puertito de Adeje could have been a model for regenerative tourism. It is becoming a monument to greenwashing and wanton destruction instead.

The question now is whether locals and the authorities will allow this pattern to continue—or whether the Canary Islands will choose a future where sustainability is more than a slogan.